Time Measured by Heaven and Machine

For millennia, human beings oriented their lives around the rhythms of the heavens. The most fundamental of these rhythms—the daily passage of the sun across the sky—served as the original clock, marking morning, noon, evening, and night with clarity. This was solar time, in which the perception of time itself expanded and contracted with the seasons.[1]

In antiquity, there was a clear distinction between telling the time of day and measuring duration. The former relied on the sun and shadows; the latter on instruments like water clocks or candles.[2] These devices measured how long something lasted—not what hour it was.

The Romans formalised solar time into twelve daylight hours and four watches of night.[3] Though unequal in length, these hours and watches brought structure to public and military life.[4]

This tradition was inherited by the monasteries of Christendom. The Rule of St. Benedict prescribed fixed times for prayer—Matins, Lauds, Prime, and so on—timed according to the sun.[5] A monk might be tasked with watching the sky, ensuring bells matched the arc of heaven.

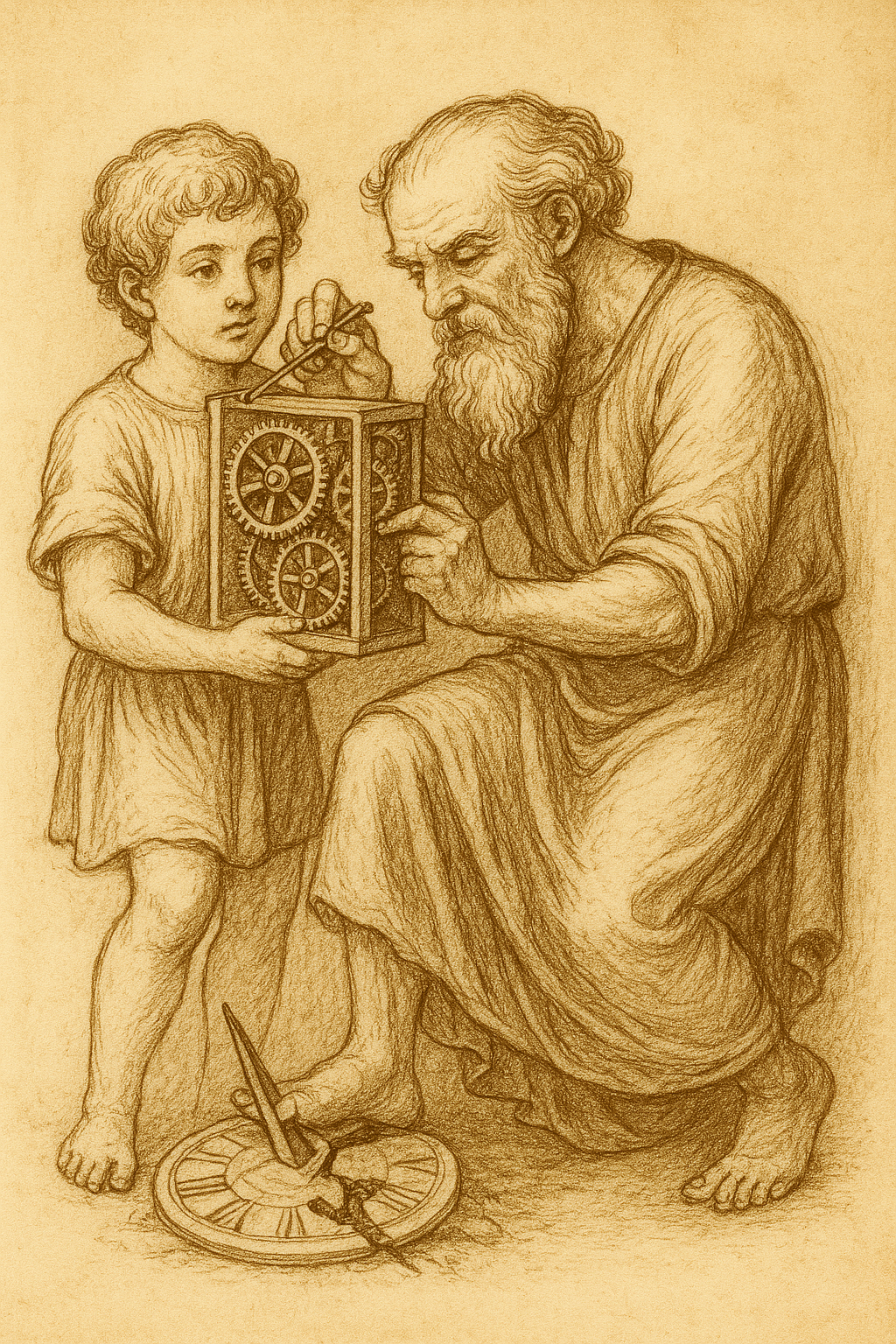

A dramatic shift occurred in the twelfth century: the Temporal Revolution. Towns and abbeys began to abandon solar observation in favour of mechanical clocks.[6] These clocks, based on interlocking gears and escapements, could not mimic solar variation—but they could reliably divide the day into 24 equal hours.

The goal was not to standardise equinoctial time but to simplify timekeeping. A singular device for tracking seasonal solar time mechanically would have required vast complexity, and further, would only function at only one latitude.[7] Equinoctial time was a technical convenience that, once adopted, became the cultural norm.

This shift unified the separate concepts of “when something happens” and “how long it takes” into a single system. One machine was now doing both.

The Industrial Revolution followed on the heels of this mechanical discipline. Work schedules, trade, and prayer conformed to bell and whistle. Regularity replaced the variability of nature.[8]

With the coming of railways, equinoctial time required standardisation. Local noon would no longer do. Britain adopted Greenwich Mean Time in 1847; the world followed in 1884.[10]

In the twentieth century, atomic clocks replaced astronomical time. Coordinated Universal Time (UTC), introduced in 1960, is based on atomic vibrations, not the sky.[11]

Timekeeping has moved from the heavens to gears to silicon. But the shadow of the sundial remains—a reminder that time was once felt as much as measured. We see experience this whenever the a leap second adjusts UTC to keep in sync with the seasons, or when daylight savings tries to keep the start of the day at a time vaguely closer to sunrise. Now, if only we had a device that would simply and reliably organise the times of day, work at any latitude, yet operate unencumbered by the constraints of mechanised timekeeping ...

Renovatio ex Traditione. Let us remember the sky.

Footnotes

- Landes, David S. Revolution in Time: Clocks and the Making of the Modern World. Harvard University Press, 1983.

- Dohrn-van Rossum, Gerhard. History of the Hour: Clocks and Modern Temporal Orders. University of Chicago Press, 1996.

- Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book II; Vitruvius, De Architectura.

- Hannah, Robert. Time in Antiquity. Routledge, 2009.

- Rule of St. Benedict, ch. 8–18; Cowdrey, H. E. J. The Cluniacs and the Gregorian Reform.

- Whitrow, G.J. Time in History. Oxford University Press, 1988.

- North, John. God’s Clockmaker: Richard of Wallingford and the Invention of Time. Hambledon and London, 2005.

- Thompson, E. P. "Time, Work-Discipline, and Industrial Capitalism", Past & Present, No. 38 (1967).

- Mumford, Lewis. Technics and Civilization. Harcourt, Brace, 1934.

- Bartky, Ian R. Selling the True Time. Stanford University Press, 2000.

- Audoin, Claude and Bernard Guinot. The Measurement of Time. Cambridge University Press, 2001.